Albert Einstein’s theories of special and general relativity have been proven time and time again. Yet a famous quote by Einstein seems to indicate that he was not 100% confident in his theories:

“No amount of experimentation can ever prove me right; a single experiment can prove me wrong.”

That quote, like so many, has been distorted and taken out of context. The more accurate story has to do with a book called 100 Authors against Einstein. He heard about the book and retorted, “If I were wrong, one would have been enough!”

Einstein had a quick wit, which may explain the numerous quotes attributed to him. But this quote, in both of its forms, can teach us a lot about the way science proves something right, and how we could apply that to other sets of ideas, such as religion.

Science as Proof

First, let's talk about an idea that is common among scientists, which is that "science can never prove something to be true." This may be what Einstein was trying to say, and it is a valuable perspective for those working in the scientific fields. However, the line between "fact" and "opinion" is blurrier than some might think. You can never be sure that your research is complete, that all questions have been answered, and no mistakes have been made. Every experiment can be retested to see if it holds true in different circumstances.

That being said, I don’t think that statement is as useful for the general population who are learning science and how it applies to their life. No one has never seen atoms with the naked eye, but scientists have done thousands of experiments that prove their existence. Physicists are still learning more about the way atoms behave, but none of them would tell you not to be confident in their research because they are only 99.9999999% sure that atoms are real. At some point, the proof is strong enough that they can confidently rely on it.

I think confusion also arises because scientists use the word “theory” to describe a set of ideas that has been successfully tested in repeated experiments, to the point where it can be used to confidently predict other results. The Theory of Gravity and the Theory of Evolution, for example, are not just good guesses, they include the most correct scientific explanations we have. We will surely learn new things that will enhance these theories, but scientists are not worried that the entire theories are wrong.

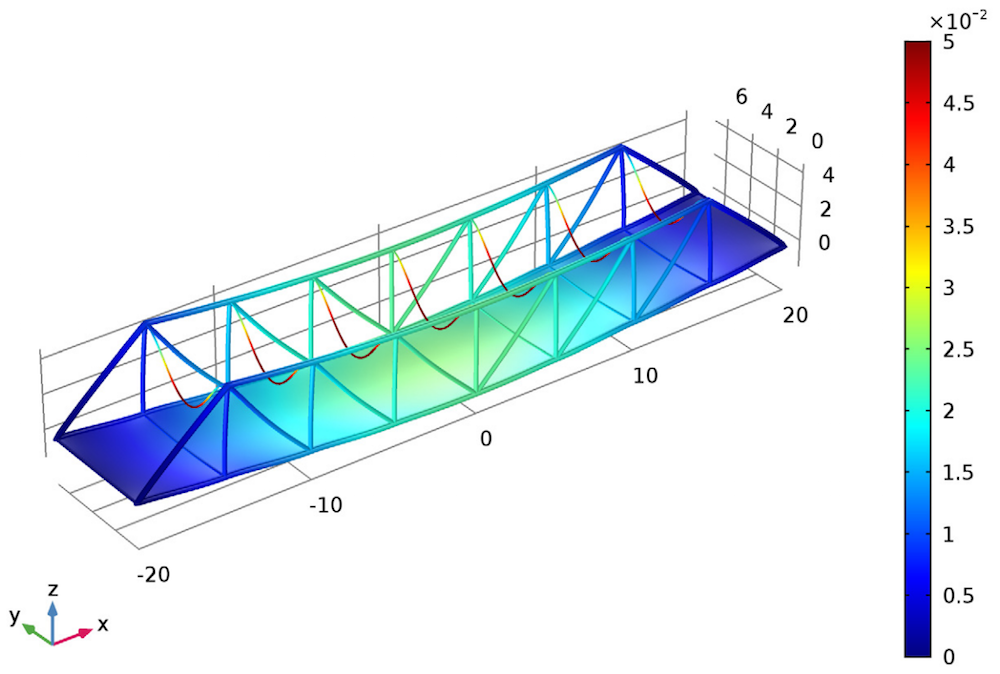

If you have been in a science class recently, you know that we often describe our knowledge of the natural world in terms of “models”. A model is a physical or mental representation of how something works. Models can illustrate relationships and structures through equations, drawings, graphs, or 3D visuals. Learning happens when our brain uses models to connect prior knowledge to new information. Because models are simplifications, virtually every model is incomplete. We don’t have a model or theory that can describe everything in the universe.

Reacting to new ideas

My last blog post explored the question of whether we can really "know" something is true. Here, I want to talk about what happens when we come across something that doesn't fit our mental model of the world, either in the field of science or religion. First I will discuss how a scientist would react to information that doesn't fit his current scientific understanding, and then we'll see if that process can help us in our search for religious truth.

We see extraordinary claims on the internet all the time, such as a drug, diet, or exercise that is a miraculous “secret to instant weight loss.” I often read headlines about experiments that supposedly “breaks the laws of Physics.” How would a scientist react to these stories? I've written five steps that they might consider as they evaluate new information.

- We can disregard the information if the experiment it came from is not valid enough to be useful.

- We can check the results of the experiment in different ways to see if there really is new information.

- We can modify our theories to account for the new data.

- We can throw out our old theories and models and create a new theory based on this evidence.

- We may not have a good explanation for the contradiction, so we can wait for further research.

Disregarding the information

Most of the “shocking” headlines you see on the internet are often exaggerated or misunderstood, like the Einstein quote I started with. To keep this sensationalism out of academic journals, there is a system of peer review, which allows other scientists to look at the data and check their work before anything is published. If an idea is so outlandish that it breaks proven laws of science, it is unlikely that anyone will even be willing to consider it. This is why patent offices refuse to look at proposals for perpetual motion machines, since it breaks the laws of thermodynamics, such as conservation of energy.

Checking the Experimental Results

When there is a peer-reviewed experiment that does seem to poke a hole in scientific theories, the next step is to try and replicate it. Repeated tests should make it clear whether the conclusions are correct or if there was an error in the original experiment. For instance, scientists recently claimed to discover faster-than-light particles, but they later found that the results were incorrect because the laboratory had a loose fiber optic cable. A more infamous example was the Cold Fusion experiment in 1989. Some researchers believed they had found a cheap, almost limitless form of atomic energy. When more careful experiments were not able to reproduce the results, it became obvious that the original research was flawed. Likewise, whenever someone claims to have discovered a new particle, scientists are wary of accepting it as true until the evidence for their hypothesis is so strong that it has less than 1 in a million chance of being incorrect. Because scientific laws work no matter which way you turn them, we are confident that thorough experiments will bring the truth into clearer focus.

Modifying our models

As I said earlier, the theories and principles that we call “laws” have that name because they have been shown to be true in many valid experiments. We add new ideas to this body of knowledge once there is enough proof. That’s how science moves forward. In fact, Albert Einstein's original theory of relativity was based on a “failed” experiment. Physicists Albert Michelson and Edward Morley had set up a detector to see how much the speed of light changed as the Earth moved in different directions through the universe. When they were not able to detect any change, Einstein hypothesized that the speed of light must be fundamental and unchangeable, while space and time can be changed. This idea was not immediately accepted, as other scientists put forth evidence that seemed to contradict his theory. Eventually, Einstein was vindicated, but only after his idea was carefully investigated through repeated experiments.

Casting aside old theories

There are times when entire theories have been overturned. For most of our history, humans believed that the Earth was the center of the universe and all other bodies revolve around us. If you hadn’t been taught otherwise, you might think this too, as it is a reasonable conclusion when looking at the sky.

This idea, called the Geocentric (earth-centered) Model, stuck so long because it worked remarkably well. An Egyptian astronomer named Ptolemy described planets that orbited the Earth with smaller movements within those circles called “epicycles.” His math explained the occasional backwards motion of planets, and it is such an accurate model that it is the basis for modern planetarium systems. We could have kept this theory and had no problem predicting the next eclipse. But to leave Earth and reach for the stars themselves, we needed a deeper understanding.

The move toward a Heliocentric (sun-centered) Model of our solar system began with Nicolas Copernicus, almost 1500 years after Ptolemy. Still, it took 100 more years to prove these ideas correct. Astronomers Tycho Brahe and Galileo Galilei made clear observations that contradicted the Geocentric Model. Based on their work, Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton developed the mathematics to prove that planets orbited the Sun by the force of gravity.

This model was not immediately accepted, as it contradicted ideas that were thousands of years old. Some of the hesitation came from religious leaders, who interpreted scriptures such as Psalms 93:1 and Joshua 10:12-13 to claim there must be a fixed Earth with the Sun orbiting it. Yet Galileo himself asserted in his famous letter to the Grand Duchess of Tuscany that his ideas were in harmony with his Christian beliefs. Isaac Newton also hoped that his research would help people believe in God.

Now, Christians accept the Heliocentric Model without being bothered by scriptures that seem to depict Earth as immovable or having “four corners.” We understand that much of this is symbolic, and it was written according to the understanding of the people living at the time. Perhaps other apparent contradictions in the scriptures will seem simpler in the future.

Waiting for further research

Any scientist will tell you that the more we learn, the more questions we find to answer. For example, Lord Rayleigh, the physicist who explained why the sky appears blue, created an equation to predict how much light a hot object will emit. While it worked well for visible light, it also predicted that the objects would give off an infinite amount of light in high-energy wavelengths. This conundrum was called the “Ultraviolet Catastrophe.” Later, another physicist, Max Planck showed the math would match our experimental observations if you assumed that light only came in small packets called “photons.”

Currently scientists are trying to figure out how much energy there is in empty space. Once again, we have a huge discrepancy between the theoretical equations and actual observations. This has been called the "Vacuum Catastrophe.” While we cannot fully explain what is happening, we know that if we keep searching, we’ll eventually find the answer.

Even in the more day-to-day sciences, like nutrition, medicine, and the environment, we see conflicts among researchers, and it’s hard to know which theory is correct. Perhaps they are partially right and partially wrong. Scientific research will someday reveal the best explanation. In the meantime, we use the models we have and take them as far as they will work.

Application to Religion

“The Desires of My Heart” by Walter Rane

For the past few years, I’ve taught high school students to think scientifically: to be skeptical of their first impressions and to seek evidence before making conclusions. I have wondered if I needed to apply this sort of thinking to my religious studies; which is why I have written this blog post.

I know that science and religion represent two distinct ways of searching for truth. They use different tools to reveal different information. However, I believe that as we search for truth in either of those realms, we can use similar processes to evaluate what information is valid and worth keeping. Therefore, I’m going to review the five steps I’ve discussed for scientific theories, and we'll see what to do when our search for religious truth uncovers things that don't fit the model we had in our head.

I know that science and religion represent two distinct ways of searching for truth. They use different tools to reveal different information. However, I believe that as we search for truth in either of those realms, we can use similar processes to evaluate what information is valid and worth keeping. Therefore, I’m going to review the five steps I’ve discussed for scientific theories, and we'll see what to do when our search for religious truth uncovers things that don't fit the model we had in our head.

Is this a valid source of information?

In the 1980’s, Mark Hofmann caused many Latter-day Saints to question their faith with newly found historical documents, which even General Authorities struggled to explain. Hofmann was not a professional historian, and all of his documents were proved to be forgeries, despite the fact they initially deceived experts in document analysis. Whether something agrees or disagrees with our prior beliefs, it is always wise to be skeptical and check its source. Sometimes it isn’t obvious how valid the source is, in which case we move to the other steps.

Have the authors come to valid conclusions based on the evidence?

Today, some of the most common criticisms of the Church are full of distortions and errors. It is helpful to go to the original material to try and understand the context for yourself. There are plenty of researchers and writers who have likely asked the same questions you have and are still confident in their testimonies. I appreciate that apologetic websites like Book of Mormon Central and FairMormon always include footnotes to scholarly resources and original source material, allowing you to do your own research as you come to conclusions.

Can you modify your assumptions based on this new information?

If you have ever taught a young child, you know how eager they are to learn. As adults, we have such a firm grip on what we know that we are sometimes unwilling to adapt our mental models. Perhaps you have a friend who was extremely strict about what they did on Sunday or what kind of media they used, only to later leave the Church entirely. I’ve heard some of these people say they were bothered by something in the Gospel Topics Essays or other new information they were not prepared for. We have to recognize that we don’t know everything, and we must be open-minded if we want to continue to gain knowledge. This reminds me of an idea in structural engineering: that the strongest materials have to find the balance between flexibility and rigidity. If they are too brittle and unwilling to give, they will shatter under stress.

There are only a few basic doctrines of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Those should be the foundation we build our beliefs upon. If we are dependent on other humans for our faith, they will inevitably let us down, as no one--not even divinely-called prophets--has been perfect, except the Savior. Our church culture, practices, and policies can change, but our core doctrine will not.

What should you do when there are no apparent answers?

The last two choices in my list describe what to do if you can’t explain a contradiction in your ideas. At this point, some people decide that the evidence against their faith is so strong, they are ready to cast aside their old beliefs and adopt new theories. As Terryl and Fiona Givens describe in their book, The Crucible of Doubt: Reflections on the Quest for Faith, this might not be as easy as it sounds.

To the would-be believer, not everything makes sense. Not all loose ends are tied up; not every question finds its answer. Latter-day Saint history can be perplexing, some parts of theology leave even the devout wondering, and not all prayers find answers. Still, many of us believe the disciples had it right. “To whom [else] shall we go?” (John 6:68) The doctrines Christ propounded were troubling, challenging, and they apparently produced in that instance more provocation than peace, perhaps more cognitive dissonance than resolution.

Staying the course takes a great effort of will. Relinquishing faith would solve some problems--but would multiply others. For how does one even begin to address the manifold experiences and tender feelings we have known, the powerful ideas and explanations our theology provides, and the visitations of peace and serenity that are balm to broken hearts like our own? Abandoning our faith because it doesn’t answer all the questions would be like closing the shutters because we can’t see the entire mountain. We know in part, Paul said (1 Cor. 13:12), looking for the flickering flame to give us a glimpse of the way ahead in the gloom. With Nephi, we readily confess: “I know that [God] loveth his children; nevertheless, I do not know the meaning of all things.” (1 Nephi 11:17) We know more than we think, even if we know less than we would like.

Many critics would have you believe that religion is a lie keeping you from the truth, but I have not found that to be the case. Science and religion are like two eyes that allow us to see the world more clearly. If I gave up one of those sources of knowledge because it was incomplete, it would be like taking out one of my eyes because something was out of focus. As I look at all sides of an issue, it is often frustrating when the answers are not clear. Rather than give up, I choose to continue seeking answers, because the evidence for my beliefs still outweighs any attacks against them.

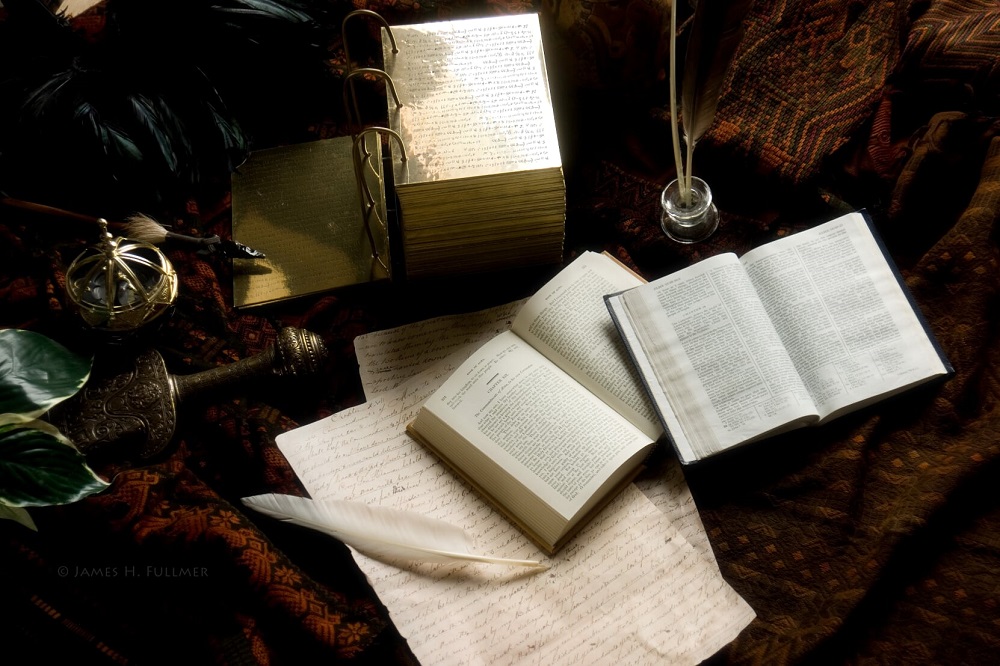

This brings me to the last point: what do you do with your questions that haven’t been answered? You can keep searching, praying, and waiting for answers. I don’t like the analogy of a “shelf” where you put your doubts to avoid thinking about them. I prefer the image of a desk, with pages of notes and stacks of open books, which reminds us to follow the process outlined in Doctrine & Covenants 88:118: seek faith diligently, teach each other wisdom out of the best books, and seek learning by study and also by faith.

|

| Book of Mormon still life by James Fullmer |

When I first started this blog post over a year ago, I didn’t realize how important it was, in both science and religion, to be willing to wait for further research. I kept hearing people at Church talk about being okay with incomplete answers. At the same time, I’d watch videos about the edges of scientific theory, and I would see how many gaps there were in our understanding, including contradictions between scientific models. These are not crises or catastrophes; they’re opportunities to learn.

I’ll end with this invitation from Jeffrey R. Holland to not give up when we face challenges:

I’ll end with this invitation from Jeffrey R. Holland to not give up when we face challenges:

In moments of fear or doubt or troubling times, hold the ground you have already won, even if that ground is limited. In the growth we all have to experience in mortality, . . . [this] desperation is going to come to all of us. When those moments come and issues surface, the resolution of which is not immediately forthcoming, hold fast to what you already know and stand strong until additional knowledge comes.

Thank you to Truman Blanchard and Andrew Cazier for their assistance in editing this article.